|

Downside Up

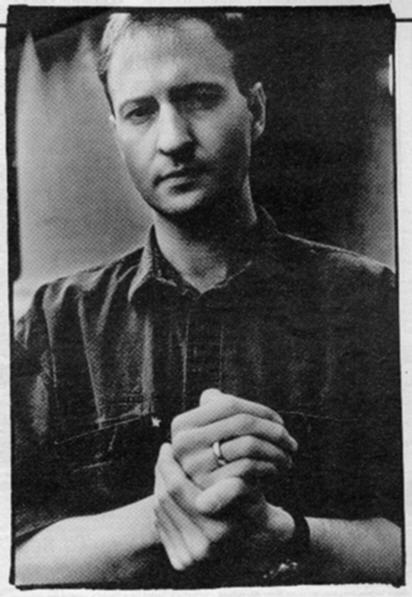

The collapse of Husker Du left BOB

MOULD bitter and hurt. After 18 months of self-imposed exile he's produced

Workbook, a

powerful inversion of his musical ideas. Interview by Brian Morton and Pam

Collins. Photograph by Tim Jarvis.

|

THE LAST days of Minneapolis power trio Husker Du were like scenes from a bad marriage. No broken hearts or plates, merely an awful, stultifying absence of passion and surprise. "It was like a ritual or routine. We'd been doing it together for nine years, and by the end it didn't really mean that much. There wasn't a challenge, there was nothing scary about it any more. Once we'd been on stage for 30 seconds, we knew exactly what was going to happen all night. The shows were good, but predictable. There were no great moments, except maybe one night towards the end and I really wish we'd stopped after that."

The music gravitates to splits like gossip columnists to divorce. What else could explain the (some thought premature) demise of one of the essential rock units of the Eighties but a power struggle? On that point, Bob Mould, former Husker Du vocalist, guitarist and chief songwriter, is fairly categorical. "It didn't interest me to be thought of as the leader of the band. I tried to play down the fact that I was writing the majority of the songs. The press were looking for things like that and it generates exactly the sort of tension that breaks up bands.

"As far as creativity was concerned, September of '87 we were getting together, bringing in material for what would have been the next record," a successor to the decidedly below-par Warehouse: Songs and Stories. "At that point, I knew it was useless."

Husker Du were notably resistant to corporate entanglements, but their very autonomy left them unanchored, prone to overwork, and their performance aesthetic was formidably self-lacerating. In the depths of their creative stall, there were two brutal interventions. Their friend and manager David Savoy took his own life only days before yet another cross-national tour that served little more than to expose the fact that drummer Grant Hart was still deeply mired in heroin abuse.

"We did about 20 more shows at the end of the year but we only did about two new songs. I'd brought in about two dozen; Grant had five or six. They weren't working; there was nothing different about them, nothing that signalled any kind of growth or change." Mould is surprisingly mild about the final imbroglio, but there is an aftertaste of rancour even in the blandest retelling of fact. "We would contribute individually. The only sense in which songs were group efforts is that three of us played them. For an album, I'd write 20 or 25 songs; Grant would write maybe six. On the actual album, I'd maybe six; he'd have five. However, there was never any question of quotas. It was very much a question of what songs everybody liked."

Mould doesn't miss the restrictive stylistic democracy of writing within the confines of an established band. He does miss the simple feedback of live performance. "That’s the last, validating step in the process. It's one of the few times when communication goes back and forth. You need that."

For the moment, though, a measure of isolation. After the break-up, Mould sequestrated himself in a Minnesota farmhouse for 18 months. The eventual result is Workbook, a markedly acoustic album with intriguing echoes (in the guitar playing and notably on the instrumental opener Sunspots) of John Fahey and (in the singing, songwriting and arranging) of imaginations as far apart as Nick Drake, John Kay and Ian Anderson.

Mould accepts that comparisons, however invidious, are unavoidable. "In an ideal world, it wouldn't happen. In the real world I fully expect people to compare it with the last work I did. As a reference point, that's fine, but there is no real comparison. Husker Du was three people who made music together for a number of years, developed a style, refined it, and ultimately got swallowed up by it. This is the beginning of something new.

"For nine years you write songs knowing how the other people play. With this, there was nobody to write for but myself. I wasn't even writing to make a record. The songs are just me, an exorcism of how tight you can wind yourself up every day before you finally explode. I spent more than a year away from everything familiar, everything I had learned was right and successful and respected and I had to learn how to sink or swim. I had to wait until I had 40 songs finished. Only then, when I had decided to make a record, did I take them to people, see who would work best with the songs."

The result is a set of dense inscapes, broodingly personal like Poison Years and Whichever Way The Wind Blows (the latter virtually a Husker song in execution), or more distanced like Compositions For The Young and Old. "I think people who understood the band, understood what the songs were about, will like it. I think people who appreciated Husker Du for the energy will have trouble with it."

The only trig point for those unwilling to take Workbook as a new beginning would be Too Far Down, Mould's acoustic Lithium anthem on the Huskers' Candy Apple Grey. There, in the album title as such as in the song, there are inklings of his new method. "I'd experimented before, but things that were written in that style for Husker Du never got recorded for anyone. I don't need them any more. They're nobody's stuff, like debris floating around in space."

It's clear that Mould's lyrics, once incomprehensibly embedded in a heavy chord mix, have taken on a considerable significance.

"I write a lot of free verse and the music comes to it, usually words first. I'll play and find something that matches with the feel of when I wrote the words. Often they don't appear in the order they were written. I write songs from found words, found ideas that I keep storing up, day after day.

"Once there's a structure, something tangible, I start to refine that into something that feels like a song or a short story. All the ideas I wrote before maybe didn't mean anything as free verse, but once they're assembled into music, they tell me what I've been thinking about. Every morning I gravitate towards my instruments, work through the day before. That tells me what I've been doing rather than dictating the form of the song; I've never sat down consciously to write a brilliant pop song. That's why I don't see it as work. It's like therapy or something."

The associationism of Wishing Well or Lonely Afternoon is consistent with a method that is improvisatory only to the point where the song declares itself. Producing Workbook, Mould maintained a fairly tight hold on the material. "Structurally, it was all real tight; tempo-wise, it's pretty strict. Not working in a band, that's how it feels comfortable to me, doing the arranging, making mistakes, being critical beforehand. Once I get the physical structure, I have something like a blueprint or a common language to communicate to other players. The actual recording for Workbook was five and a half weeks from beginning to end. A week of band tracks, two weeks of me doing everything I did, three days of cello, and two weeks to mix."

Mould got together drummer Anton Fier from The Golden Palominos, and Pere Ubu bassist Tony Maimone, together with cellist Jane Scarpantoni, a classically trained player who works with Tiny Lights. "I knew there was going to be a cello on the record because I was hearing it in most of the songs. That seemed to fit and to be the thing that tied everything together. I kept hearing it, its expressiveness. It's a sound you don't get on Hammond organ or trumpet.

"We spent two weeks rehearsing and the dynamics were changing all the time. With Brasilia Crossed With Trenton the vocal is completely different from what I imagined. That was a first take and it gave the exact sensation I'd had when I wrote the song, in contrast to the way it came out in the demo studio."

Much of what Husker Du did was rough-hewn, magnificent in its way but locked into a cycle of diminishing creative return. Mould seems at last to have tapped into his own unconscious. Where once - on Land Speed Record or Zen Arcade or Metal Circus - the conception was static, almost ideological, with that surface roughening of spontaneity, on Workbook (an altogether more finished and lyrically audible project than anything Husker Du attempted), you can hear Mould thinking, establishing his structures at the very moment he subverts them. When before he used dynamite, these days he employs a wholly convincing musical and imaginative logic. Even when they tip towards nightmare, the songs have the cadence of dream. "What I'm looking forward to now is finding other ways of putting things together, waiting for it to hit me."

Reproduced from "Cut" magazine, August 1989

[Bob Mould Index] *** [Husker Du Index] *** [Sugar Index]